Confined polymer physics

In many modern electronics and structural materials, polymers are often confined to nanoscopic dimensions, which change their mechanical properties relative to bulk conditions. These confinement effects can arise due to changes in chain mobility – whereas free surfaces (for instance in thin films) can accelerate chain mobility and soften the polymer matrix, substrates and fillers (for instance in nanocomposites) can decelerate chain mobility and stiffen the polymer matrix. In the Keten group at Northwestern, I used molecular dynamics simulations to study the extent and length-scale of such nanoconfinement effects in common industrial polymers.

Coarse-grained modeling

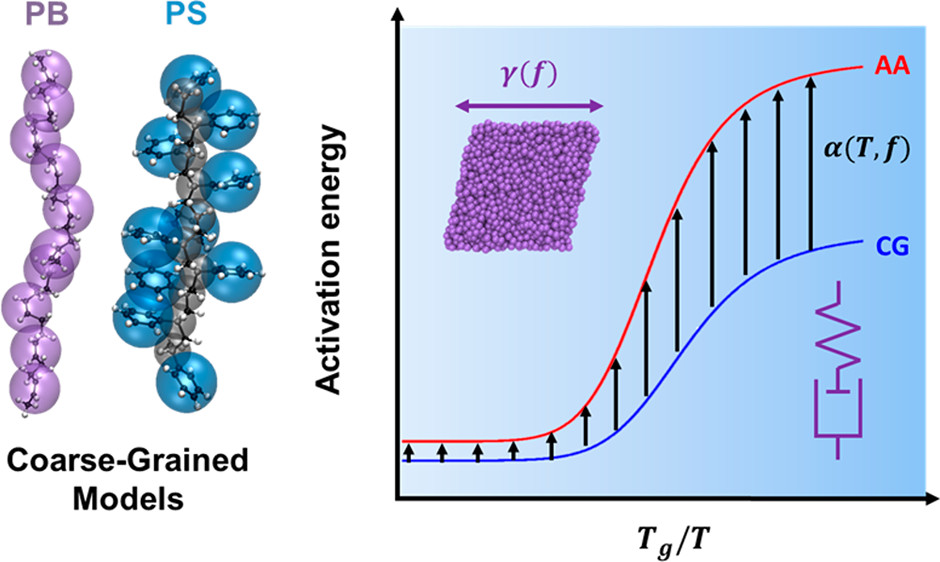

Nanoconfinement effects can occur over tens of nanometers, which is beyond the length-scale accessible using conventional atomistic simulation techniques. An approach to circumvent this problem is to utilize coarse-grained models that reduce the structural degrees-of-freedom, which allows tractable simulations of materials which are hundreds of nanometers in size. However, such coarse-graining methods will necessarily result in inaccurate dynamical properties relative to atomistic systems. To address this problem. Wenjie Xia and I developed a coarse-graining algorithm for polymers in which the interaction potential of the coarse-grained model is “renormalized” to the atomistic model based on their glassy dynamics and cage mobility. We successfully developed models for the thermoplastic polystryrene [1], the rubbery polymer polybutadiene [2], and molecular glass forming liquid ortho-terphenyl [3].

Representative coarse-grained images of polybutadiene and polystyrene, taken from Song et al [2].

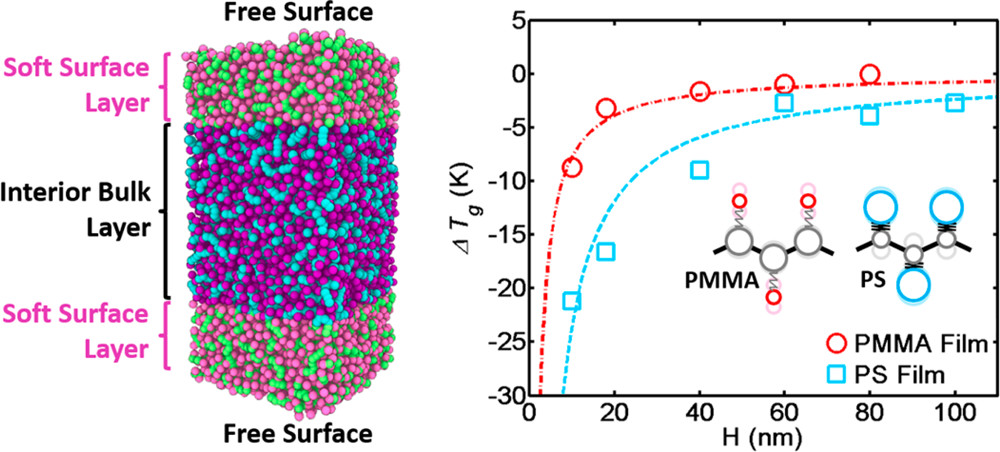

Nanoconfinement effects on chain mobility

Next, using these models, we studied the dynamics of polymers under different confinement effects arising from free surfaces, polymeric substrates, and rigid substrates and fillers. We demonstrated that polymer architecture can play a significant role in the nanoconfinement effect, as polymers with bulkier side-chains undergo a greater increase in chain mobility under free-surface confinement [4], but a smaller decrease in chain mobility under substrate confinement [5]. We also demonstrated that a large interphase region can exist when both of these polymers form a soft interface with each other [6].

Representative free-standing thin film configurations, taken from Hsu et al [4].

Nanomechanical characterization

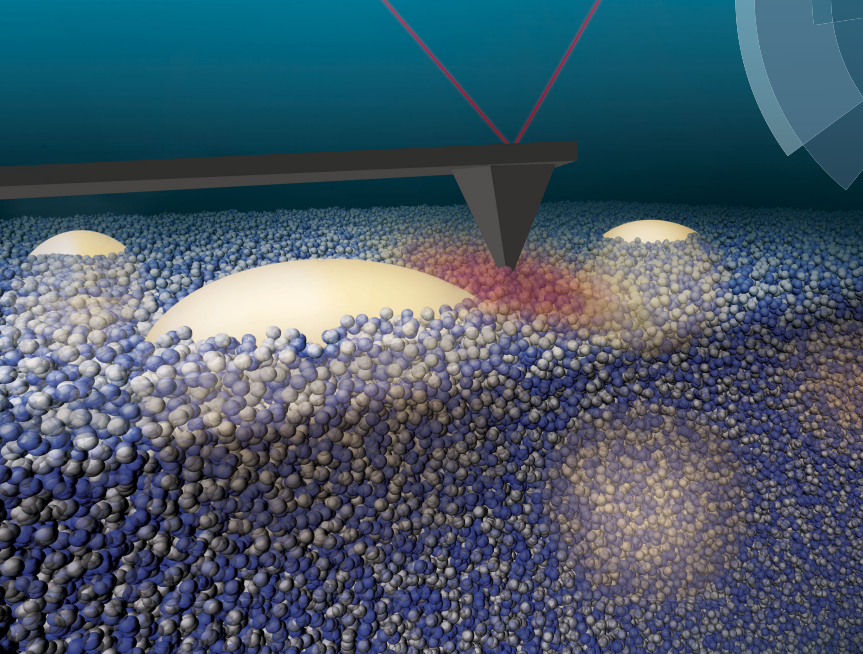

Lastly, we used these models to study the nanoscale mechanical response of substrate and filler-confined thin films using indentation – a common experimental approach to quantify the interphase length-scale. We showed that indentation techniques can overestimate the interphase length-scale due to the stress field propagation arising from the indentation [7], an effect which can be exacerbated at elevated temperatures due to viscous flow at higher temperatures [8].

Illustration of the nanoindentation study which was selected as the front cover of Soft Matter, taken from Song et al [8].

References

- Xia, W.*, Song, J.*, Jeong, C., Hsu, D. D., Phelan, F. R., Douglas, J. F., & Keten, S. “Energy Renormalization for Temperature Transferable Coarse-Graining of Polymer Dynamics”. Macromolecules. 50(21), 8787-8796 (2017)

- Song, J., Hsu, D. D., Shull, K. R., Phelan Jr, F. R., Douglas, J. F., Xia, W., & Keten, S. “Coarse-Grained Modelling of Polymer Viscoelasticity via Energy Renormalization.” Macromolecules. 51(10), 3818-3827 (2018)

- Xia, W., Song, J.., Krishnamurthy, N., Phelan Jr, F. R., Keten, S., & Douglas, J. F. “Energy Renormalization for Coarse-Graining the Dynamics of a Model Glass-Forming Liquid”. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 122(6), 2040-2045 (2018)

- Hsu, D. D., Xia, W., Song, J., & Keten, S. “Glass-Transition and Side-Chain Dynamics in Thin Films: Explaining Dissimilar Free Surface Effects for Polystyrene vs Poly(methyl methacrylate)”. ACS Macro Letters. 5, 481-486 (2016)

- Xia, W., Song, J., Hsu, D. D., & Keten, S. “Side-Group Size Effects on Interfaces and Glass Formation in Supported Polymer Thin Films”. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 146(20), 203311 (2017)

- Hsu, D. D., Xia, W., Song, J., & Keten, S. “Prediction of Local Glass Transition Temperature of Polystyrene and Poly(methyl methacrylate) Bilayer Thin Films”. MRS Communications. 7(4), 832-839 (2017)

- Xia, W.*, Song, J.*, Hsu, D. D., & Keten, S. “Understanding the Interfacial Mechanical Response of Nanoscale Polymer Thin Films via Nanoindentation”. Macromolecules. 49(10), 3810-3817 (2016)

- Song, J.*,Kahraman, R.*, Collinson, D.*, Xia, W., Brinson, L. C., & Keten, S. “Temperature Effects on the Nanoindentation Characterization of Stiffness Gradients in Confined Polymers”. Soft Matter. 15(3), 359-370 (2019)